Talcum Powder Cancer Evidence

Talcum Powder Cancer Trials Have Produced an Abundance of Discovery from Internal Johnson & Johnson Documents Showing that the Company Knew Baby Powder Had an Asbestos Problem

1976: J&J Withholds Asbestos Test Results from FDA

A 1976 FDA Review of Talc Safety by the FDA Fails to Even Reach OSHA Standards

In 1976, concern over the safety of talc-based cosmetics reached a crescendo. For the first time since the 1930's, federal regulators considered adopting rules on talc used in cosmetics and personal care products. Until this time, talc use was entirely unregulated in the cosmetics industry, despite gathering concerns about its potential threat to health. Johnson & Johnson was strongly invested in preserving its freedom to use talc in its products, as well as maintaining Baby Powder' reputation as harmless for daily use - even on babies.

The main topic of debate at the FDA in 1976 centered around determining an acceptable, safe level of asbestos content in the raw talc supply used to make talcum powder and similar personal care products. OSHA standards, long since in place, dictated 1% as the asbestos content limit for raw talc used in manufacturing. The FDA discussed adopting this level but ultimately decided that a standard applied to miners was not good enough for babies.

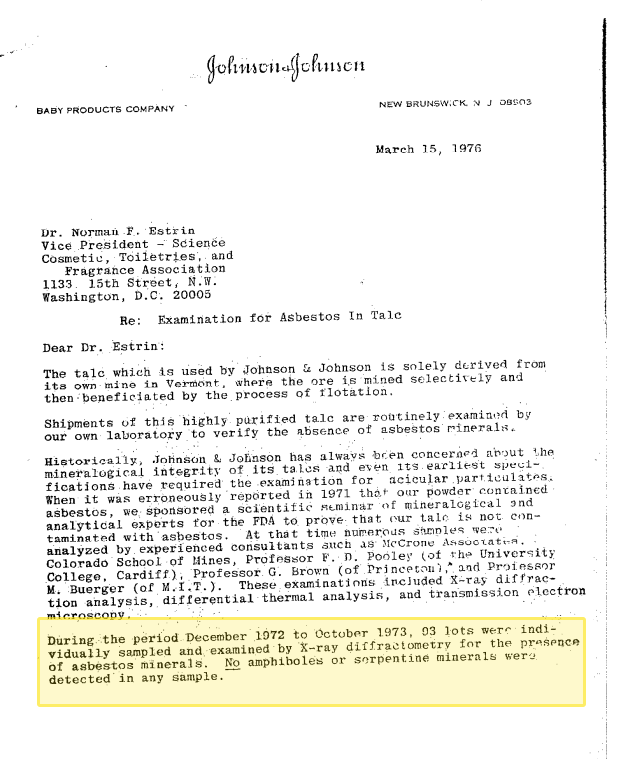

As part of an information gathering process, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration requested recent asbestos test results from Johnson & Johnson's raw talc supply. The company chose to share test results from a 9-month span beginning nearly four years earlier, in December 1972. During this period of time, the company assured federal regulators, no asbestos had been "detected in any sample" of its raw talc supply.

What the company didn't disclose turns out to be much more important than what it did share with federal regulators: At least three different tests of raw talc used for baby powder came back positive for asbestos between 1972 and 1975.

What the company didn't disclose turns out to be much more important than what it did share with federal regulators: At least three different tests of raw talc used for baby powder came back positive for asbestos between 1972 and 1975. These tests were completed by three different labs. J&J officials purposefully chose to withhold these test results in its report to the FDA. The test results proving asbestos existed in at least some of J&J's raw talc supply originated from the months leading up to December of 1972 and those directly following that span.

The company outwardly made its best attempt to downplay the need for any cosmetic talc regulation. Meanwhile, internally, J&J executives were fretting about the reputation of their brand based on emerging research. Based on evidence produced in 2018 talc trials, the company employed various tactics including: commissioning its own, favorable research studies and publishing them widely; honing in on a not-too-sensitive testing method that would allow for a degree of asbestos content; and actively marketing their product as safe for everyday use.

In the end, the FDA's consideration of new regulation for cosmetic talc resulted in no regulation whatsoever because no consensus could be reached. The talcum powder industry remains unregulated to this day.

J&J Avoids Talc Safety Research to Protect Brand Reputation

A 1976 FDA Review of Talc Safety by the FDA Fails to Even Reach OSHA Standards

In the 1970s, emerging research began to draw a connection between talc and two specific ailments: lung disease and cancer. Concerned this information would reach the public and damage the reputation and sales of Johnson's Baby Powder, Johnson & Johnson executives set several different efforts in motion designed at framing talcum powder in a positive light.

From well-funded marketing campaigns urging Americans "a sprinkle a day keeps the odor away", to bankrolling favorable research and withholding compromising test result from the FDA, the company engaged in questionable practices to preserve the reputation of its crown jewel, Baby Powder.

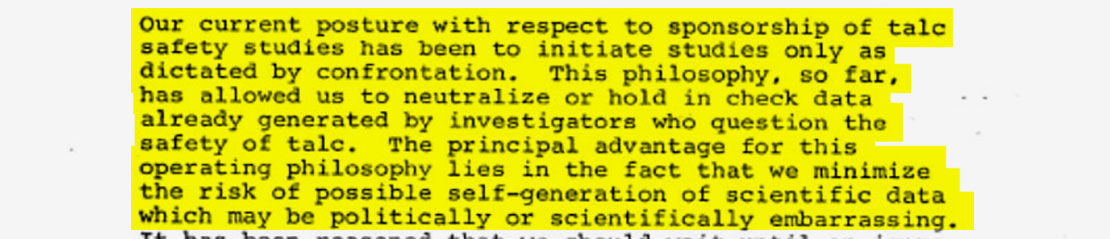

One such strategy that has become public knowledge through the course of talcum powder lawsuits filed by ovarian cancer victims is the company's approach to talc safety research. In a March 3, 1975 memo labeled as HIGHLY CONFIDENTIAL, Johnson & Johnson's Director of Research spelled out an approach that would, "minimize the risk of possible self-generation of scientific data which may be politically or scientifically embarrassing":

A defensive tactic which aimed to "neutralize or hold in check" data that brought the safety of talc under scrutiny, the approach dictated the company would only conduct research when forced to do so. In other words, it was best not to closely examine the safety of talc because the company knew it might create data that made a case against its own product.

This short memo, which was addressed to managers of the baby products division, speaks volumes:

First, it establishes the fact that J&J executives were well aware of contemporary research showing talc exposure led to increased rates of cancer and lung disease.

Secondly, it shows the company had no actual interest in warning consumers of the risk. There was significant concern over the damage this research may do to the company's sacred cow product, Baby Powder--but not over the damage Baby Powder may do to mothers, babies, or others to whom it was marketed. The terms "politically or scientifically embarrassing" are particularly revealing; for most people, the risk of a deadly disease such as cancer would be much more than "embarrassing". The use of this term shows an appalling lack of concern for humanity

Third, this short memo gives sense of just how far J&J was prepared to go to product the reputation of its product. With an inkling that their product caused severe side effects, the company would actively choose not to look into the problem any further. As we now know, many efforts to downplay research and promote the safety of talc would be embraced over the coming decades. It has only been in the past year that American consumers have gained insight into the internal operations of Johnson & Johnson concerning talcum powder safety.

J&J Can't Say Talc Has "Always" Been Safe

Internal Johnson & Johnson Document Shows J&J Aware of Asbestos in Talcum Powder

As of spring of 2019, Johnson & Johnson was facing more than 12,000 talcum powder lawsuits filed by women alleging their ovarian cancer diagnosis was linked to using talcum powder for feminine hygiene. Throughout the course of the litigation, which dates back to 1999, company officials have insisted their talcum powder products were safe.

Yet a number of documents, ranging from tests results to internal memos, show the company has been long since anxious about protecting the reputation of Johnson's Baby Powder and Shower-to-Shower. Even today, when these documents have reached the public, J&J executives blindly insist their products have always been safe for routine use. Several juries have disagreed, awarding tens of millions in damages to victims of ovarian cancer.

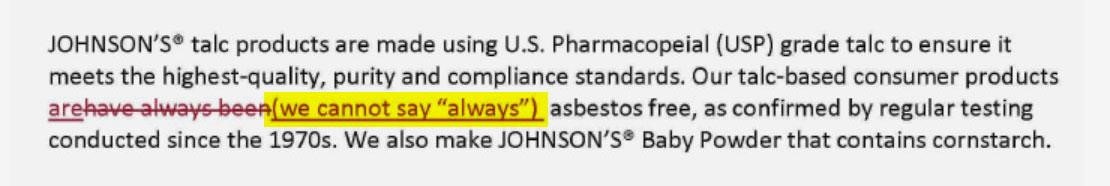

This particular document, dating back to 2013, is an internal markup of content from the J&J website. The paragraph is clearly intended to establish the safety of talc, saying Johnson's talc-based products meet "the highest-quality, purity and compliance standards". Nevermind the cosmetic industry is entirely unregulated in the United States, and there are no "compliance standards". The correction made in this paragraph is most glaring. The first version of the website read,

Our talc-based consumers products have always been asbestos free, as confirmed by regular testing conducted since the 1970s.

An editor re-wrote this sentence to remove the blanket term "always", noting in parentheses, we cannot say "always". The statement was changed to read,

Our talc-based consumers products are asbestos free, as confirmed by regular testing conducted since the 1970s.

The amended version oddly implies test results since the 1970s have shows products to be asbestos-free, but doesn't outright say it. The notation itself--swapping out "always" for a present tense safety assurance--indicates company officials are aware their products have been tainted by asbestos in the past. And the test results dating back to the 1970s support the assertion that J&J talc-based products have, at times, contained asbestos.

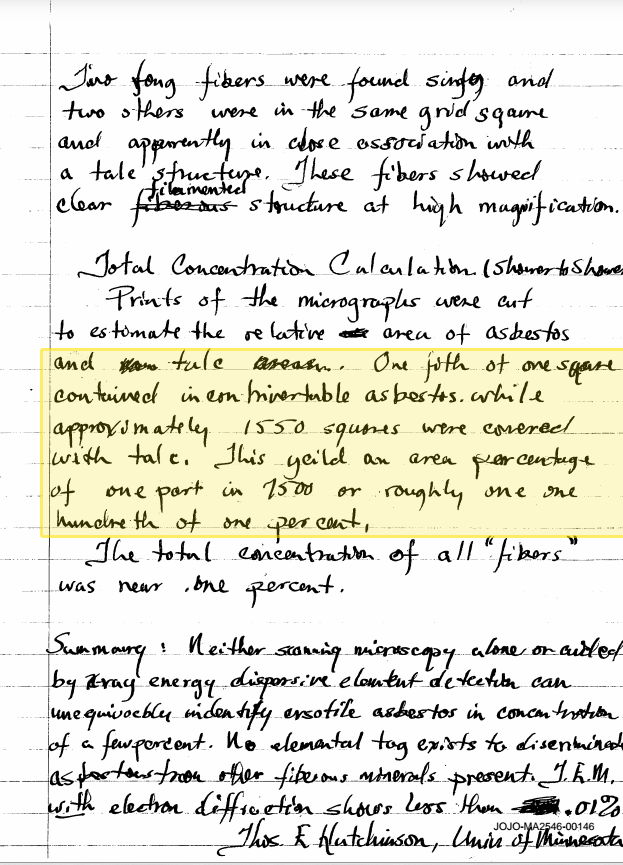

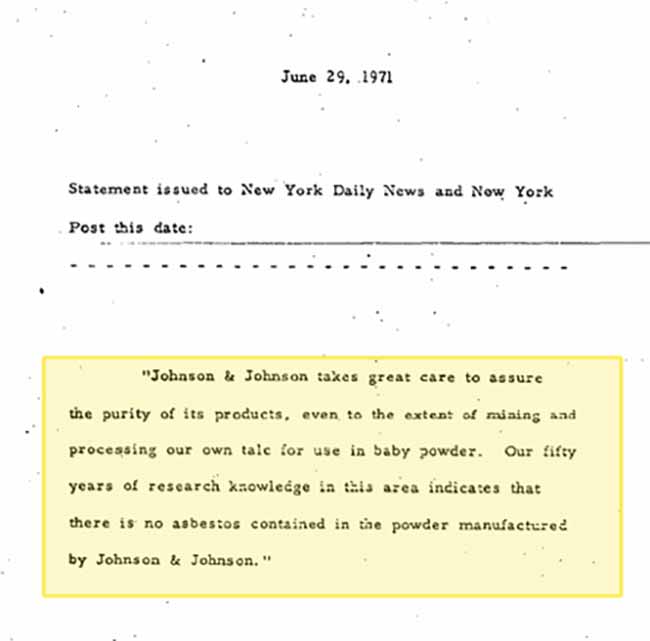

For example, a researcher at the University of Minnesota found "incontrovertible asbestos" in J&J talc products in 1972. In 1973, J&J research director DeWitt Peterson asserted doubts that pure talc could ever be produced: no final product will ever be made which will be totally free of respirable particles. These are just two of the many examples where J&J officials were clearly aware of emerging research linking talcum powder use to cancer and lung disease. And just as J&J executives and legal representatives state today, company executives claimed talcum powder was safe in the early 1970s. A statement issued by J&J and printed in the New York Daily News in 1971 asserted, "Our fifty years of research knowledge in this area indicates that there is no asbestos contained in the powder manufactured by Johnson & Johnson."

Three Labs Detect Asbestos in J&J Talc in Early 1970s

Independent Labs Find Asbestos in J&J Talc, Consultant Tells Company It's "Rather High"

In 1976, the FDA strongly considered adopting talc safety regulations for cosmetics. Learning of the possible presence of asbestos particles in raw talc supplies, federal regulators were concerned about potential health risks such as lung disease and cancer that the use of products such as Baby Powder may pose to women and infants.

One method the FDA used to collect data on the matter was to ask J&J to submit results of recent tests analyzing raw talc for asbestos fibers such as tremolite and actinolite. The results of these tests were intended to aid regulators in determining an acceptable level of asbestos content in raw talc.

In retrospect, it is clear J&J carefully selected from among several years of test results to share only those that came back negative for asbestos fibers. The results the company shared with the FDA spanned a short period from December 1972 to October 1973. The cover letter stated that asbestos had not been "detected in any sample" taken during that time period. What the company did not disclose is that numerous samples taken before and after that short window did come back positive for asbestos fibers. The following three tests were conducted at three different labs in the five years leading up to the FDA report; none was mentioned to the FDA and only came to light through recent litigation:

1972: University of Minnesota Researcher Finds Asbestos in Shower-to-Shower

In 1972, Thomas E. Hutchinson, a researcher at the University of Minnesota, used an electron microscope to analyze talc product samples submitted by Johnson & Johnson. Hutchison discovered "incontrovertible asbestos", as he put it, in the sample of Shower-to-Shower provided. We now have access to images of the slides he examined, which clearly point out various types of asbestos particles. The results of this particular study were not shared with the FDA.

1973: Johnson & Johnson Reviews Talc Test Results

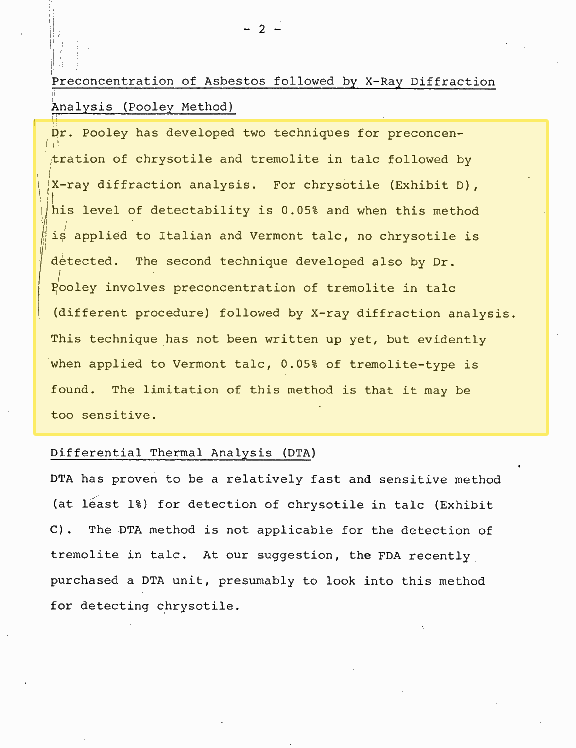

Another piece of information J&J did not share with the FDA in 1976 was an internal review of its own talc safety testing. This 1973 comparison between two asbestos test methods indicates asbestos was found in J&J samples. Both of the methods involve concentrating talc samples prior to testing, "followed by X-ray diffraction analysis".

In one method, no asbestos particles are detected. But in the second, 0.05 "tremolite-type" asbestos particles are found in a samples from the company's Vermont mine. The writer warns the second method may be "too sensitive", implying the company would opt for a less-sensitive method that was less likely to detect asbestos in raw talc.

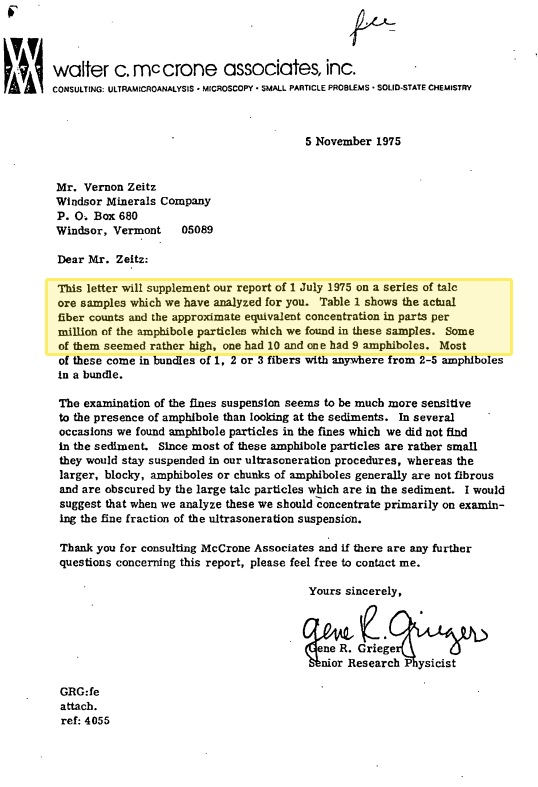

1975: Consultant Finds "Rather High" Asbestos Content in Talc Supply

The third of the most damning test results J&J chose not to share with the FDA in 1976 was the report of a consultant hired by Windsor Minerals, a subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson, to assess asbestos levels in supply originating from its Vermont talc mine. The consultant notes finding "rather high" asbestos levels in the talc samples he tested. He uses the term "amphiboles" to refer to clusters of asbestos fibers he found.

"Antagonistic Personalities"

J&J Labels Researchers Who Identify Asbestos in Talcum Powder as "Antagonist"

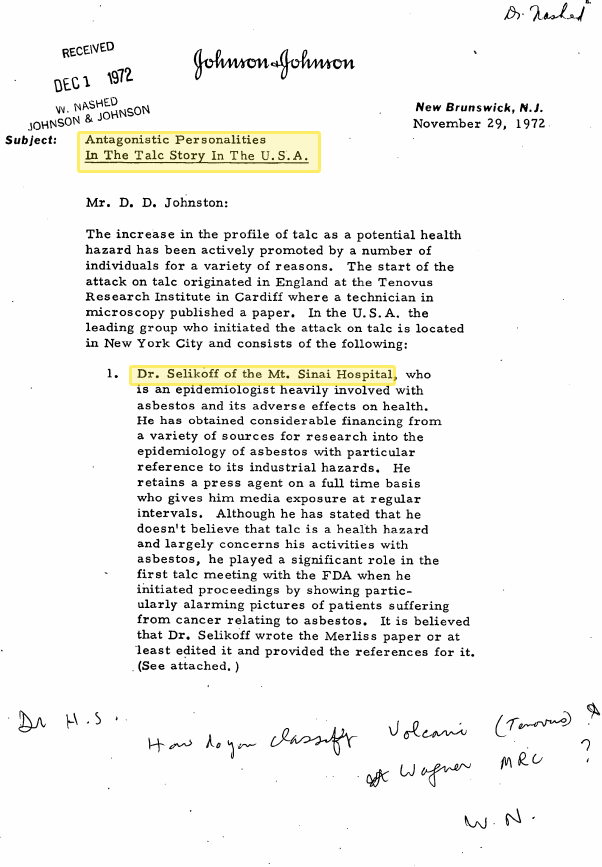

In a 1972 internal memo entitled "Antagonistic Personalities In The Talc Story In The U.S.A.", J&J identified six specific individuals who posed a threat to the future of talc-based cosmetic products. The memo references "the attack on talc", a battle between the company and outside researchers over the safety of talc for use in personal care products.

The memo states, "the increase in the profile of talc as a potential health hazard has been actively promoted by a number of individuals for a variety of reasons." The implied message of the memo is that the motivation of these researchers is not honest, and that the reputation of talc is to be protected regardless of research findings that may point to serious health concerns such as cancer from asbestos contamination.

The memo identifies a group of medical researchers and advocates based in New York City as the leading force driving what it frames as anti-talc efforts. This group consisted of:

- Dr. Irving Selikoff, Dr. Arthur Langer, and other unnamed colleagues at Mount Sinai Hospital

- Jerome Kretchmer, director of the EPA of New York who was seeking to be elected Mayor on a health platform, and Harold Romer, an engineer at the EPA of New York

- Dr. Alfred Weissler at the FDA

- Dr. Seymour Lewin, Professor of Analytical Chemistry at NYU

Dr. Irving Selikoff, according the the 1972 memo, was an epidemiologist specifically concerned with the health effects of asbestos. While targeting talc specifically was not his focus, it was a well-known fact at the time that naturally-occurring talc deposits frequently also contain traces of asbestos. Dr. Selikoff presented his findings regarding the effects of asbestos on human health at the FDA's first meeting on the safety of talc. The memo notes he started the meeting by sharing, "particularly alarming pictures of patients suffering from cancer related to asbestos". Dr. Selikoff received significant funding to probe into the health dangers of asbestos in industrial settings and frequently published his research, according to the memo.

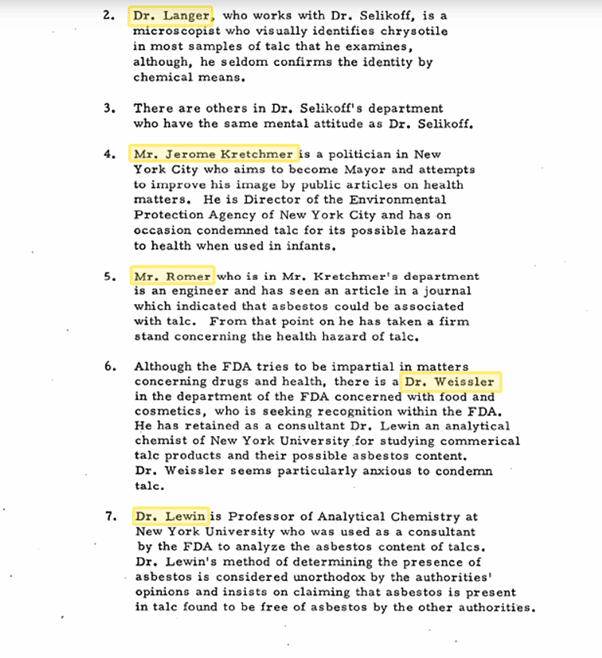

Dr. Arthur Langer was the only colleague of Dr. Selikoff to be mentioned by name in the memo, though it is implied that Mount Sinai Hospital is generally "antagonistic". According to the memo, Dr. Langer "visually identifies chrysotile in most samples of talc he examines". Chrysotile is the most commonly-found form of asbestos and is now considered a known carcinogen. The memo stated Dr. Langer identified the fibers by microscope only, but did not confirm his results by "chemical means".

Jerome Kretchmer and Harold Romer of the New York Environmental Protection Agency made the list because both had gone on the record identifying talc as a health risk. The memo implies Jerome Kretchmer's interest in promoting talc as a risk to infants is a political tactic to "improve his image" and build momentum for his mayoral candidacy. Harold Romer purportedly read a journal article on the presence of asbestos in talc and was taking a public stance on the health dangers of talc.

Finally, the memo references Dr. Alfred Weissler of the FDA and Dr. Seymour Lewin of NYU as working in collaboration to bring the topic of talc dangers to the fore at the FDA. The memo notes that, "Dr. Weissler seems particularly anxious to condemn talc," and that Dr. Romer employs, "unorthodox" procedures for detecting asbestos in talc.

At the point this memo was written, asbestos had already been detected in J&J's primary cosmetic talc supply and the health dangers of asbestos inhalation were becoming accepted from an industrial standpoint. This particular memo identifies individuals who were working to translate the growing awareness of the dangers of commercial talc to the issues of cosmetic talc products such as baby powder.

1971: J&J Claims Powder to be Asbestos-Free

Despite Knowledge of Talc Tests Positive for Asbestos, Johnson & Johnson Tells the FDA Otherwise

When asked by FDA regulators in 1971 about the potential presence of asbestos in its talc-based body powders, Johnson & Johnson published an official statement claiming the products did not contain asbestos: "Our fifty years of research knowledge in this area indicates that there is no asbestos contained in the powder manufactured by Johnson & Johnson." There is ample evidence to show the company knew this statement to be false, and in fact had already spent considerable energy worrying about and devising various solutions to the problem.

By the early 1970s, the connection between asbestos fiber inhalation and lung disease was well recognized. OSHA created workplace safety regulations to limit asbestos exposure to workers, which included those involved in talc mining as well as those manufacturing products containing talc.

Around this time, a group of researchers at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York identified a new conundrum: They were finding asbestos particles in lung tissues of deceased patients who had never worked in an industry related to asbestos. Aware that asbestos fibers were commonly found in talc deposits, these researchers began to look into talcum powder as a potential exposure point.

It was at this time that the FDA started to seriously consider adopting regulations for the cosmetic use of talc. If workers mining talc and manufacturing products made with talc were experiencing the negative effects of asbestos exposure, it stood to reason consumers were also being exposed. Testing revealed that two cosmetic talc products from two unidentified brands were found to contain asbestos.

This startling information was brought to President Nixon and the FDA. Federal regulators opened an inquiry that would last several years. Until this time, products such as Johnson's Baby Powder were revered as essential to the nurturing and care of an infant, and this new information threatened the product's revered status.

Johnson & Johnson replied to FDA inquiries with a strong statement designed to establish their opinion as fact: "Our fifty years of research knowledge in this area indicates that there is no asbestos contained in the powder manufactured by Johnson & Johnson." The company cited its "fifty years of research knowledge" but failed to disclose that Tremolite asbestos fibers had, in fact, been detected in the raw talc supply used for its cosmetic products.

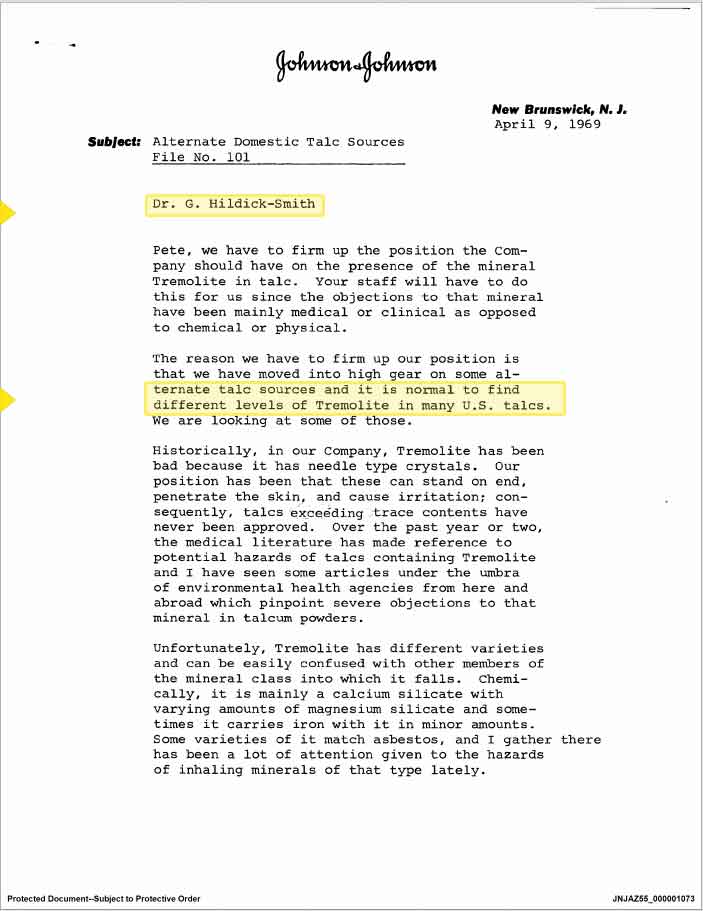

It was just four years prior, in 1967, that J&J's executive, William Ashton, had written, "it is normal to find different levels of Tremolite in many U.S. talcs" and acknowledge asbestos fibers had been detected in the company's Vermont talc mines. At that time, Ashton exchanged correspondence with the company doctor and other advisors on a safe or tolerable asbestos content level and the potential health concerns for mothers and babies.

This is one of several examples where an outward statement made by the company is now known to be questionable or false, based on internal company communications and test results that have been made public through talcum powder litigation.

J&J Claims Just 1% Asbestos in Talc

J&J Representative Tells Federal Regulators Its Talc Has Less Than 1% Asbestos, Comapny Knows Better

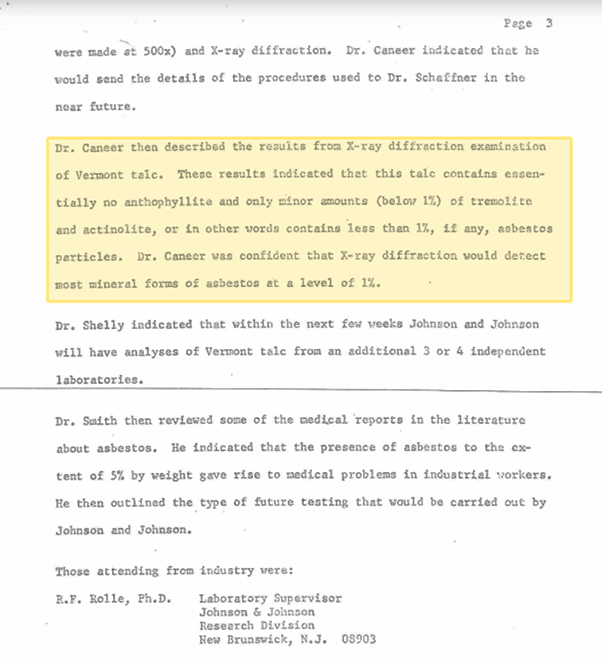

In 1971, Johnson & Johnson executives were called before a meeting of federal regulators at the FDA to share their expertise on talc. The FDA sought to compile information on the presence of asbestos in the nation's raw talc supply as a step toward understanding potential health risks of talc-based cosmetics. J&J's representative, a Dr. Caneer, assured regulators the company talc supply contained "less than 1%, if any, asbestos particles". Yet J&J officials knew this statement to be false at the time and, in fact, would continue to detect asbestos in its cosmetic talc supply in the ensuing years.

In the early 1970s, a new awareness of the dangers of asbestos led the FDA to consider the risks posed by talc. Talc deposits in nature are commonly contaminated with asbestos, and the newly-formed OSHA had recently set safety standards for workers encountering asbestos in the mines. Federal regulators of food and drugs followed suit by launching an inquiry into the potential for asbestos in talc-based cosmetics such as Johnson's Baby Powder.

In July of 1971, Johnson & Johnson was called to report its talc findings to the FDA. A team of scientists and doctors representing J&J presented their fundings, stating that test results had showed the company's raw talc supply contained "less than 1%, if any, asbestos".

A Reuter's investigation published in December of 2018 tells the whole story. Whereas perhaps one test showed little to no asbestos content, it is clearly documented that a number of other tests, both conducted internally and by outside labs between the years 1971 and the early 2000s, tested positive for asbestos. The Vermont mine where J&J sourced the majority of its talc supply was found to contain asbestos in 1967.

What's more, a paper trail of memos, reports, and other internal documents shows the company actively worried over the asbestos content in its talc. In some cases, company officials expressed concern about the health risks to mothers and babies, but, by and large, the company seemed most concerned with a potential threat to the reputation of their sacred Baby Powder. A strategy for avoiding creating "embarrassing" research finding was devised, and there are numerous examples of J&J hiding compromising test results or only telling a part of the story. In no case was the company proactive in warning the public or federal regulators about the dangers it suspected and to this day does not admit asbestos has ever contaminated its baby powder.

1967: Asbestos Discovered in J&J Talc Supply

Company Discusses Safety Risk of Tremolite Asbestos Fibers

Before the risk of asbestos on raw talc became a concern among federal regulators in the 1970s, internal communications from Johnson & Johnson reveal the company was aware Tremolite asbestos particles had been detected in its cosmetic talc supply by the mid 1960s. As a result, the company discussed potential health risks of asbestos exposure and explored safe tolerance levels for asbestos in talc for adults and infants. Additionally, the company doctor suggested a potential for talc litigation related to asbestos in the future.

In 1964, Windsor Metals Inc., a subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson, purchased several talc mines in Vermont. These mines provided both the talc used in cosmetic products such as Johnson's Baby Powder and Shower-to-Shower, as well as a lesser grade of talc sold to other manufacturers for use in construction products and other types of manufacturing.

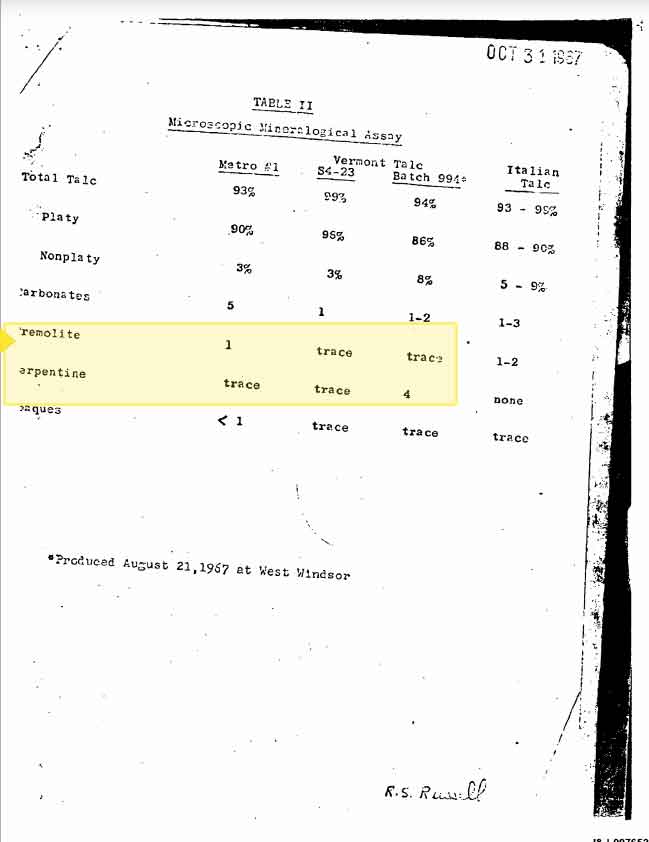

Testing from Windsor's Vermont mines revealed the presence of two indicators of asbestos, tremolite and arpentine, in 1967. The following table was included in a 1967 internal memo authored by J&J executive William Ashton:

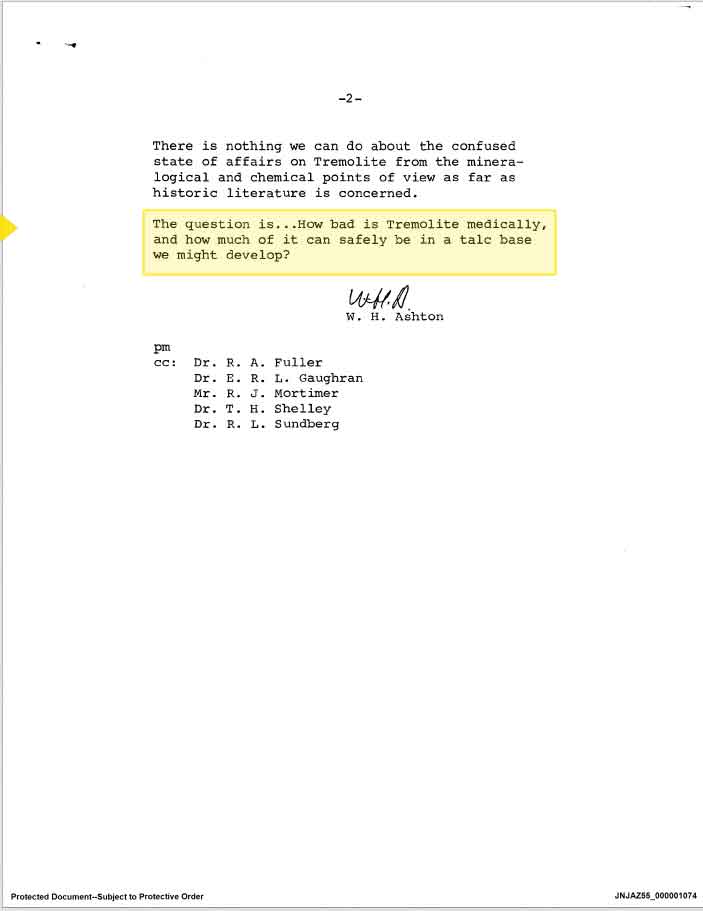

At this time, asbestos-type fibers were regarded as undesirable because they resulted in a scratchy, rather than smooth and silky, baby powder. The company sought other raw talc sources that were more pure, but by 1969, was seeking to justify the use of asbestos-tainted talc because it appeared to be commonplace or "normal" in the domestic supply. In a 1969 communication to a small leadership team considering Alternative Domestic Talc Sources, J&J's executive, Ashton, acknowledged the company's past approach of seeking to avoid tainted talc ("Historically, in our company, Tremolite has been bad…") and queried, "How bad is Tremolite medically, and how much of it can safety be in a talc base we might develop?"

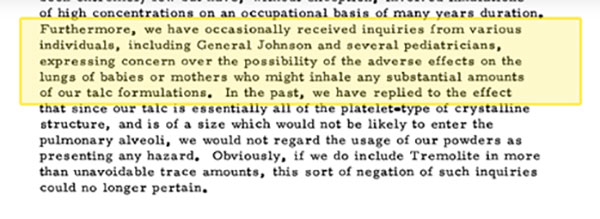

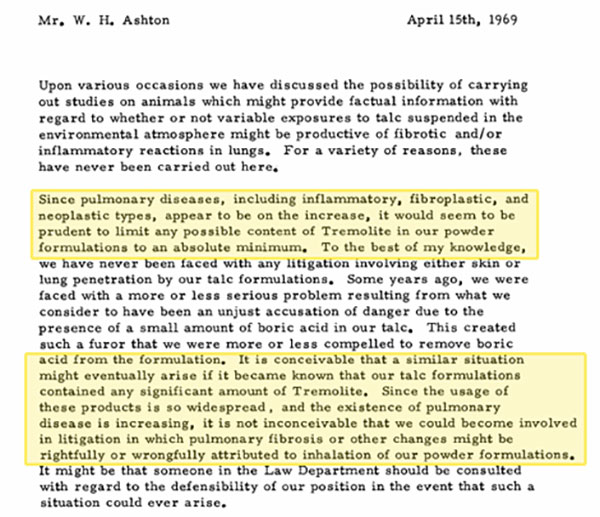

In his reply, the company physician raised concerns about the risk of lung disease and cancer from asbestos exposure, and cautioned that it made sense "to be prudent to limit any possible content of Tremolite" to an "absolute minimum". Robert Wood Johnson II, who was the son of the founder and by then had retired, also weighed in on the topic, sharing his concerns about "the possibility of adverse effects on the lungs of babies or mothers".

The company physician had, in fact, been in communication with concerned pediatricians by this time. He wrote that J&J's official response to pediatricians thus far had been that, "we would not regard the usage of our powders as presenting any hazard." However, he cautioned that the company could not make these same safety claims if their products marketed for babies were to "include Tremolite in more than unavoidable trace amounts":

Dating back to 1969, these letters represent the first correspondence now in the public domain in which J&J officials discuss the presence of asbestos fibers in its talc supply as a health risk. The company doctor's letter, dated March 15, 1969, goes on to predict the potential for future litigation on the matter:

It is clear from this communication that by 1969:

- Johnson & Johnson's main supply of cosmetic talc was tainted by asbestos fibers;

- The company was aware exposure to asbestos fibers had been linked to lung disease and cancer;

- The company knew it had to limit asbestos fibers if it wanted to claim its products were safe for babies.

Yet raw talc from the Vermont mine would be used for decades to come to make Johnson's Baby Powder.

Austin, TX

Baltimore, MD

Birmingham, AL

Boston, MA

Buffalo, NY

Chicago, IL

Cincinnati, OH

Cleveland, OH

Columbus, OH

Dallas, TX

Denver, CO

Detroit, MI

Fresno, CA

Hartford, CT

Honolulu, HI

Houston, TX

Indianapolis, IN

Jacksonville, FL

Kansas City, MO

Las Vegas, NV

Los Angeles, CA

Louisville, KY

Memphis, TN

Miami, FL

Milwaukee, WI

Minneapolis, MN

Nashville, TN

New Orleans, LA

New York, NY

Oklahoma City, OK

Orlando, FL

Philadelphia, PA

Phoenix, AZ

Pittsburgh, PA

Portland, OR

Providence, RI

Richmond, VA

Riverside, CA

Rochester, NY

Sacramento, CA

Salt Lake City, UT

San Antonio, TX

San Diego, CA

San Francisco, CA

San Jose, CA

Seattle, WA

St. Louis, MO

Tampa, FL

Tucson, AZ

Tulsa, OK

Virginia Beach, VA

Washington, DC

Alaska

Arizona

Arkansas

California

Colorado

Connecticut

Deleware

Florida

Georgia

Hawaii

Idaho

Illinois

Indiana

Iowa

Kansas

Kentucky

Louisiana

Maine

Maryland

Massachusetts

Michigan

Minnesota

Mississippi

Missouri

Montana

Nebraska

Nevada

New Hampshire

New Jersey

New Mexico

New York

North Dakota

Ohio

Oklahoma

Oregon

Pennsylvania

Rhode Island

South Carolina

South Dakota

Tennessee

Texas

Utah

Vermont

Virginia

Washington

West Virginia

Wisconsin

Wyoming